|

| Matthew Hopkins, the Essex witch finder. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons |

A European phenomenon

Between 1400 and 1800 between forty and fifty thousand people, mainly women, died in Europe and colonial north America on charges of witchcraft. Europeans had long believed in witches yet only in the period after 1500 did they turn this cultural assumption into a one of the major killers of western Europe.

What is witchcraft?

Belief in magic has always been common and exists in the world today, for example in Africa. But what is unique to western Christian civilization is the belief in a personal devil. There were two quite different but related activities denoted by the word witchcraft as it was used in early modern Europe: the practice of maleficium, and worshipping the devil. Maleficium meaning calling down a curse on another, was the effect of witchcraft. The cause was the pact with the devil. It was usually believed that those witches who made pacts with the devil also worshipped him collectively in nocturnal ceremonies, the ‘witches’ sabbath’ that could include naked dancing or the cannibalism of infants.Witchcraft as inversion

Almost everybody believed in witches and it was heresy to doubt their existence. In his book Thinking with Demons (Oxford, 1999), Stuart Clark argues that views on witchcraft arose from notions of ‘misrule’ or inversion: wisdom/folly; male/female; Carnival/Lent. In a world of ‘looking-glass logic’ structured by opposition and inversion, demonic witchcraft made sense. Witchcraft had all the appearance of a proper religion, but in reality it was a religion perverted. The pact with the devil was a parody of baptism. The witches’ Sabbath was a parody of the mass (or of Protestant preaching). A further inversion lay in the fact that witches could change themselves into animals.The Malleus Maleficarum

In 1484 Pope Innocent VIII authorized two German Dominican Inquisitors, Heinrich Krämer and Jakob Sprenger, to hunt witches in nearby areas of southern Germany. Krämer oversaw the trial and execution of several groups – all of them women – but local authorities objected to his use of torture and banished him. While in exile, he wrote the classic text on witchcraft, the Malleus Maleficarum (Hammer of Witches) (full text here), published in 1486. These views and activities were endorsed in a papal bull of 1484. The book proved the catalyst to give shape to existing anxieties. In 1532 Charles V’s new codification of imperial law, the Lex Carolina, prescribed the death penalty for both heretics and witches. Far from abandoning belief in witchcraft as a relic of Catholic superstition, Protestants endorsed it and quoted Exodus 22:18: 'Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live'.Witchcraft and popular belief

Witchcraft was both intellectual and folk belief. People in the early modern village were subject to a huge range of hazards – plague, illnesses and sudden deaths. The distinctions between the natural and the supernatural were blurred and within the community individuals with special powers – cunning folk – were recognized. It was natural to ascribe relatively unusual or inexplicable events such as slow lingering illnesses, mental illness, hailstones to maleficium. Most of the quarrels between ‘witch’ and victim involved a denial of neighbourliness or some other perception of a wrong done. The majority of witchcraft accusations came from below and concentrated on the alleged harm done by maleficium. It was their social superiors who added the element of diabolism.Why women?

Although men and boys were indicted, a disproportionate number of those brought before the courts were post-menopausal women, notably widows. They were poor, lacking male protectors, and the victims of a misogynistic culture. Women were seen as by nature weaker than men and therefore had a greater capacity to fall; they could not grasp spiritual matters easily and were credulous and impressionable in their beliefs; at the same time they were resentful of authority and discipline and their carnal appetites were greater than men’s. Since Eve they had been the devil’s preferred target.Other historians have drawn attention to the changing social situation of women that marginalized them in society – for example an increase in the number of women living alone as spinsters or widows, and perhaps as well a decline in neighbourliness. Moreover, women’s customary roles gave them more opportunities to practise harmful magic as they generally served as cooks, midwives and healers. Older women and widows were victims of the hatred and fear felt for the woman past childbearing years whose body has become an object of disgust. Envious of young women, she gives vent to her spite through harmful magic.

The women who admitted to witchcraft did so often under torture but in some cases they seem to have believed their own stories.

Scotland: a case study

Witchcraft had been on the Scottish law books from 1563, but went virtually unprosecuted until 1590 when James VI became an enthusiastic prosecutor. In 1590 he was caught up in storms when on his way to meet his bride, Anne of Denmark, and on his return he led an investigation into the witchcraft that had ‘caused’ the storms. Between November 1590 and May 1591 more than a hundred suspects were examined and a large number were executed. He uncovered a story of a gathering at North Berwick parish kirk the previous Halloween over which the devil had presided with the intention of planning the king’s destruction through manipulation of the weather. The accused confessed under torture and were executed.In 1591 he commissioned the publication of News from Scotland, which outlined the recent events, presumably for an English audience. But he also wanted to write something more scholarly and to challenge Reginald Scot’s 1584 treatise The Discoverie of Witchcraft. In 1597 he published his Demonologie.

The Act of 1604

However, by the time this was published, James' belief in witchcraft seems to have been waning. When he became king of England he backed new legislation (1604) that defined witchcraft as a felony. The Act took witchcraft prosecutions out of the church courts and into the secular courts, exposing them to the normal rules of evidence and substituting hanging for burning at the stake. In practice, with one conspicuous exception (see below) witchcraft prosecutions declined during James reign. (But Macbeth was presumably meant as a tribute to his zeal in uncovering witches.) But though prosecutions declined in England, they intensified in Scotland and between 1590 and 1680 about a thousand people were executed. This can be seen as part of the Kirk’s power struggle against the secular authorities.The Pendle witches

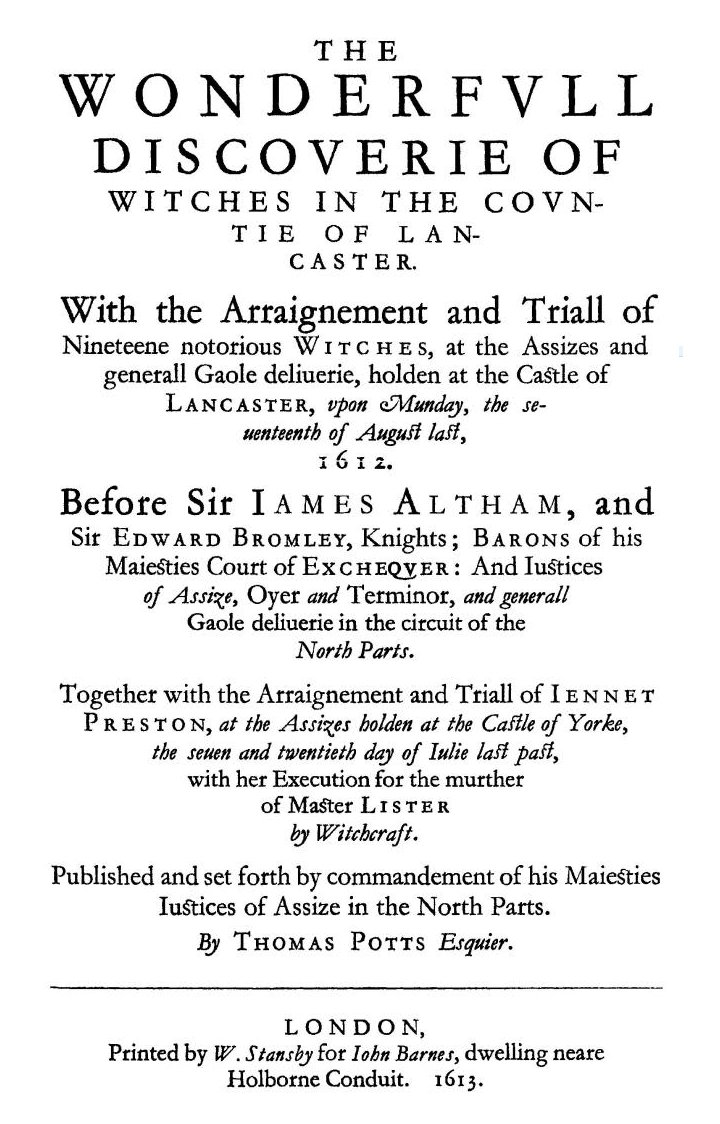

|

| "Potts" by ElinorD - Facsimile reprinted in modern Carnegie Publishing edition of the books. Licensed under Public domain via Wikimedia Commons |

The interrogations unearthed the following ‘facts’. Elizabeth Sowthernes confessed to having made a pact with the devil twenty years before, after which she was regularly visited by a spirit called Tibb, who sucked her blood. With the aid of clay images she had used witchcraft to harm her enemies, including a local man who refused to let her on his land. Her daughter, Elizabeth Device, was marked out as a witch by having one eye lower than the other with a strange squint. She confessed to having a spirit named Ball in the shape of a brown dog, which she baptised. She was indicted for killing three men by witchcraft. Her son James confessed to having a spirit called Dandy, which he used to kill a man who had refused him the gift of an old shirt. Anne Whittle (Chattox) said she allowed to devil to suck on her ribs and participated in a spirits’ banquet. Her familiar appeared to her as ‘Fancie’ and helped her drive cows mad or kill them.

Nine women and two men were executed. See here for the full story. There is another full account here, where you can also find details of the confessions.

The East Anglian witch scare

See here for the details. The witch scare was the produce of the extreme circumstances of the English Civil War. Two minor gentlemen, Matthew Hopkins and John Sterne were allowed to hunt out 'witches', unchecked by the local magistrates, who would normally have wished to follow the proper procedures of English law. When it emerged that Hopkins was charging well in excess of the normal rate for fees and expenses, he became discredit, and was unmasked by a strong-minded clergyman who published an exposé. It was a short-lived panic that cost the lives of about a hundred people.The decline of witchcraft

Witchcraft prosecutions declined in most parts of Europe from the end of the seventeenth century, when the scientific revolution and the coming of the Enlightenment provided a new view of the world with naturalistic explanations for death and disasters.The last witch to be hanged in England was Alice Molland, who was sent to the gallows in Exeter in 1684. In 1727 Janet Horne was the last witch to be executed in Scotland.

The Act of 1735 made it a crime for anyone to claim that any person had magical powers or was guilty of practising witchcraft.

The last person to be tried under the act was the fraudulent medium, Helen Duncan, in 1944.

No comments:

Post a Comment